The Middle Byzantine period followed a period of crisis for the arts called the Iconoclastic Controversy, when the use of religious images was hotly contested. Iconoclasts (those who worried that the use of images was idolatrous), destroyed images, leaving few surviving images from the Early Byzantine period. Fortunately for art history, those in favor of images won the fight and hundreds of years of Byzantine artistic production followed.

The stylistic and thematic interests of the Early Byzantine period continued during the Middle Byzantine period, with a focus on building churches and decorating their interiors. There were some significant changes in the empire, however, that brought about some change in the arts. First, the influence of the empire spread into the Slavic world with the Russian adoption of Orthodox Christianity in the tenth century. Byzantine art was therefore given new life in the Slavic lands.

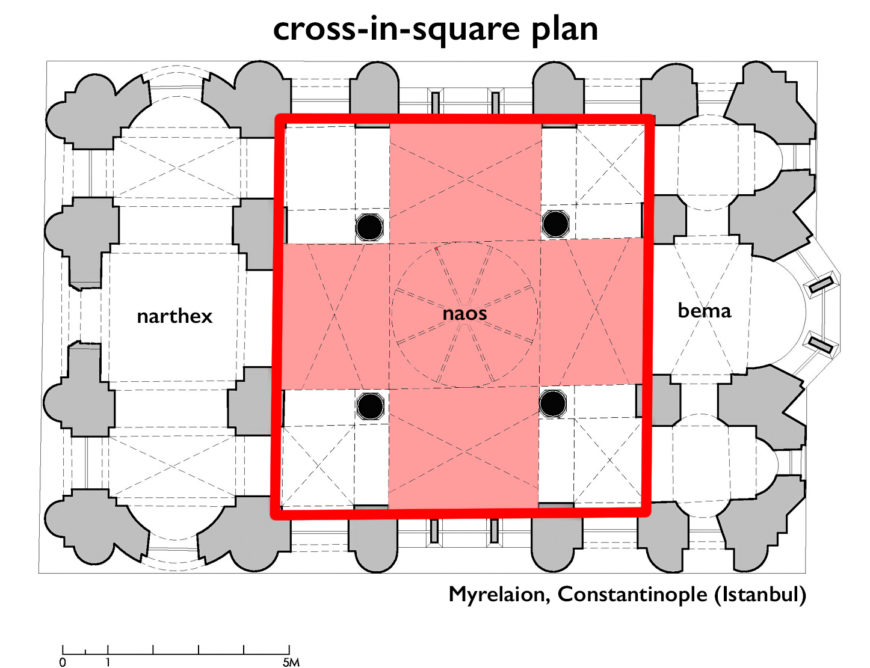

Architecture in the Middle Byzantine period overwhelmingly moved toward the centralized cross-in-square plan for which Byzantine architecture is best known.

These churches were usually on a much smaller-scale than the massive Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, but, like Hagia Sophia, the roofline of these churches was always defined by a dome or domes. This period also saw increased ornamentation on church exteriors. A particularly good example of this is the tenth-century Hosios Loukas Monastery in Greece.

This was also a period of increased stability and wealth. As such, wealthy patrons commissioned private luxury items, including carved ivories, such as the celebrated Harbaville Tryptich, which was used as a private devotional object. Like the sixth-century icon discussed above (Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George), it helped the viewer gain access to the heavenly realm. Interestingly, the heritage of the Greco-Roman world can be seen here, in the awareness of mass and space. See for example the subtle breaking of the straight fall of drapery by the right knee that projects forward in the two figures in the bottom register of the Harbaville Triptych (left). This interest in representing the body with some naturalism is reflective of a revived interest in the classical past during this period. So, as much as it is tempting to describe all Byzantine art as “ethereal” or “flattened,” it is more accurate to say that Byzantine art is diverse. There were many political and religious interests as well as distinct cultural forces that shaped the art of different periods and regions within the Byzantine Empire.