Minoan palace centers were divided into numerous zones for civic, storage, and production purposes; they also had a central, ceremonial courtyard.

The most well known and excavated architectural buildings of the Minoans were the administrative palace centers.

When Sir Arthur Evans first excavated at Knossos, not only did he mistakenly believe he was looking at the legendary labyrinth of King Minos, he also thought he was excavating a palace. However, the small rooms and excavation of large pithoi, storage vessels, and archives led researchers to believe that these palaces were actually administrative centers. Even so, the name became ingrained, and these large, communal buildings across Crete are known as palaces.

Although each one is unique, they share similar features and functions. The largest and oldest palace centers are at Knossos, Malia, Phaistos, and Kato Zakro.

The Complex at Knossos

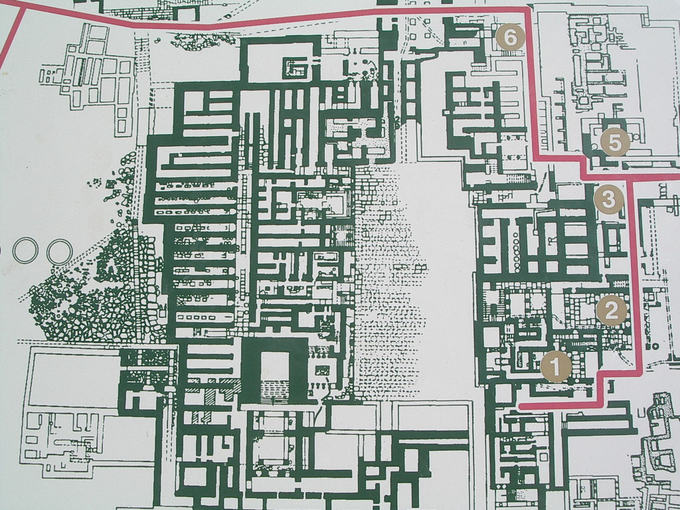

The complex at Knossos provides an example of the monumental architecture built by the Minoans. The most prominent feature on the plan is the palace’s large, central courtyard. This courtyard may have been the location of large ritual events, including bull leaping, and a similar courtyard is found in every Minoan palace center.

Several small tripartite shrines surround the courtyard. The numerous corridors and rooms of the palace center create multiple areas for storage, meeting rooms, shrines, and workshops.

The absence of a central room and living chambers suggest the absence of a king and, instead, the presence and rule of a strong, centralized government.

The palaces also have multiple entrances that often take long paths to reach the central courtyard or a set of rooms. There are no fortification walls, although the multitude of rooms creates a protective, continuous façade. While this provides some level of fortification, it also provides structural stability for earthquakes. Even without a wall, the rocky and mountainous landscape of Crete and its location as an island creates a high level of natural protection.

The palaces are organized not only into zones along a horizontal plain, but also have multiple stories. Grand staircases, decorated with columns and frescos , connect to the upper levels of the palaces, only some parts of which survive today.

Wells for light and air provide ventilation and light. The Minoans also created careful drainage systems and wells for collecting and storing water, as well as sanitation.

Their architectural columns are uniquely constructed and easily identified as Minoan. They are constructed from wood, as opposed to stone, and are tapered at the bottom. They stood on stone bases and had large, bulbous tops, now known as cushion capitals. The Minoans painted their columns bright red and the capitals were often painted black.

Phaistos

Phaistos was inhabited from about 4000 BCE. A palatial complex, dating from the Middle Bronze Age , was destroyed by an earthquake during the Late Bronze Age. Knossos, along with other Minoan sites, was destroyed at that time. The palace was rebuilt toward the end of the Late Bronze Age.

The first palace was built about 2000 BCE. This section is on a lower level than the west courtyard and has a nice facade with a plastic outer shape, a cobbled courtyard, and a tower ledge with a ramp that leads up to a higher level.

The old palace was destroyed three times in a time period of about three centuries. After the first and second disaster, reconstruction and repairs were made, so there are three, identifiable construction phases. Around 1400 BCE, the invading Achaeans destroyed Phaistos, as well as Knossos. The palace appears to have been unused thereafter.

The Old Palace was built in the Protopalatial period. When the palace was destroyed by earthquakes, new structures were built atop the old. In one of the three hills of the area, remains from the Neolithic era and the Early Minoan period have been found.

Two additional palaces were built during the Middle and Late Minoan periods. The older one looks like the palace at Knossos, although the Phaistos complex is smaller. On its ruins (probably destroyed by an earthquake around 1600 BCE), the Late-Minoan builders constructed a larger palace had several rooms separated by columns.

Like the complex at Knossos, the complex at Phaistos is arranged around a central courtyard and held grand staircases that led to areas believed to be a theater, ceremonial spaces, and official apartments. Materials such as gypsum and alabaster added to the luxurious appearance of the interior.