When Egypt had military and political security and vast agricultural and mineral wealth, its architecture flourished. As the pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom restored the country’s prosperity and stability, there was a resurgence of building projects. Grand tombs in the form of pyramids continued to be built throughout the Middle Kingdom, along with villages, cities, and forts. The reign of Amenemhat III is especially known for its exploitation of resources, in which mining camps—previously only used by intermittent expeditions—were operated on a semi-permanent basis. A vast labour force of Canaanite settlers from the Near East aided in mining and building campaigns.

Ancient Egyptian architects used sun-dried bricks, fine sandstone, limestone, and granite for their building purposes. As in the Old Kingdom, stone was most often reserved for tombs and temples, while bricks were used for palaces, fortresses, everyday houses, and town walls. Mud was collected from the nearby Nile River, placed in moulds, and left to dry and harden in the hot sun until they formed bricks for construction. Architects carefully planned all their work, fitting their stones and bricks precisely together. Hieroglyphic and pictorial carvings in brilliant colours were abundantly used to decorate Egyptian structures, and motifs such as the scarab, sacred beetle, solar disk, and vulture were common.

The “Black Pyramid” of Amenemhat III

The Black Pyramid, the first to house both the pharaoh and his queens, was built for Amenemhat III (r. 1860–1814 BCE). It is one of the five remaining pyramids of the original eleven pyramids at Dahshur in Egypt. Originally named Amenemhet is Mighty, the pyramid earned the name “Black Pyramid” for its dark, decaying appearance as a rubble mound. Typical for Middle Kingdom pyramids, the Black Pyramid, although encased in limestone, is made of mud-brick and clay instead of stone. The ground-level structures consist of the entrance opening into the courtyard and mortuary temple, surrounded by walls. There are two sets of walls; between them, there are ten shaft tombs, which are a type of burial structure formed from graves built into natural rock. The capstone of the pyramid was covered with inscriptions and religious symbols.

Workers’ Villages and Forts

Workers’ villages were often built nearby to pyramid construction sites. Kahun (also known as El-Lahun), for example, is a village that was associated with the pyramid of Senusret II. The town was laid out in a regular plan, with mud-brick town walls on three sides. No evidence was found of a fourth wall, which may have collapsed and been washed away during the annual inundation. The town was rectangular in shape and was divided internally by a mud-brick wall as large and strong as the exterior walls. This wall divided about one-third of the area of the town, and in this smaller area, the houses consisted of rows of back-to-back, side-by-side, single-room houses. The larger area, which was higher up the slope and thus benefited from whatever breeze was blowing, contained a much smaller number of large, multi-room villas, indicating perhaps a class separation between workers and overseers. A major feature of the town was the so-called “acropolis” building; its column bases suggest its importance.

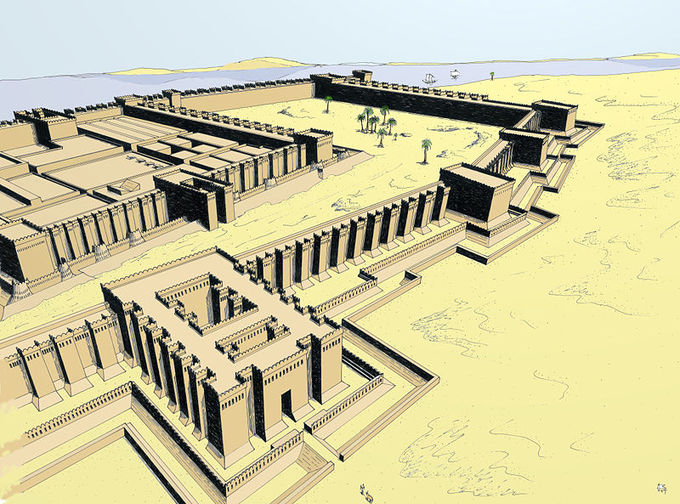

Senusret III was a warrior-king who helped the Middle Kingdom reach its height of prosperity. In his sixth year, he re-dredged an Old Kingdom canal around the first cataract to facilitate travel to upper Nubia, using this to launch a series of brutal campaigns. After his victories, Senusret III built a series of massive forts throughout the country to establish the formal boundary between Egyptian conquests and unconquered Nubia. Buhen was the northernmost of a line of forts within signalling distance of one another. The fortress itself extended more than 150 meters along the west bank of the Nile, covering 13,000 square meters, and had within its wall a small town laid out in a grid system. At its peak, it probably had a population of around 3500 people. The fortress also included the administration for the whole fortified region. Its fortifications included a moat three meters deep, drawbridges, bastions, buttresses, ramparts, battlements, loopholes, and a catapult. The walls of the fort were about five meters thick and ten meters high.

The Karnak Temple Complex

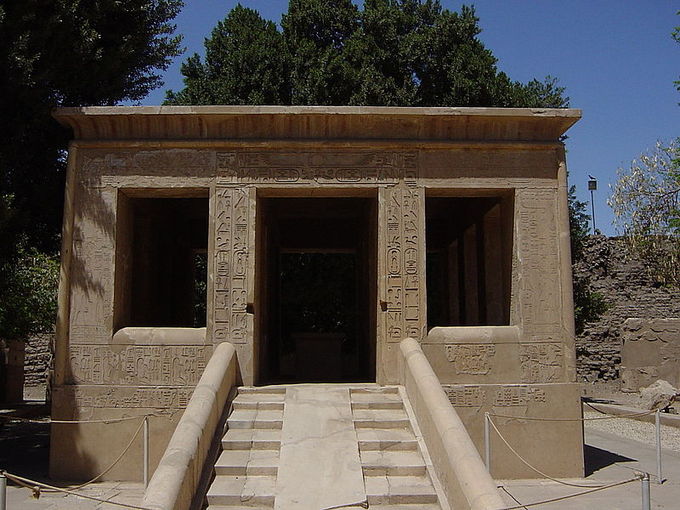

The Karnak Temple Complex is an example of fine architecture that was begun during the Middle Kingdom and continued through the Ptolemaic period. Built by Senusret I, it was comprised of a vast mix of temples, chapels, pylons, and other buildings. The White Chapel – also referred to as the Jubilee Chapel – is one of the finest examples of architecture during this time. Its columns were intricately decorated with reliefs of very high quality. Later in the New Kingdom, the Chapel was demolished; however, the dismantled pieces were discovered in the 1920s and carefully assembled into the building that is seen today.

Stelae of the Middle Kingdom

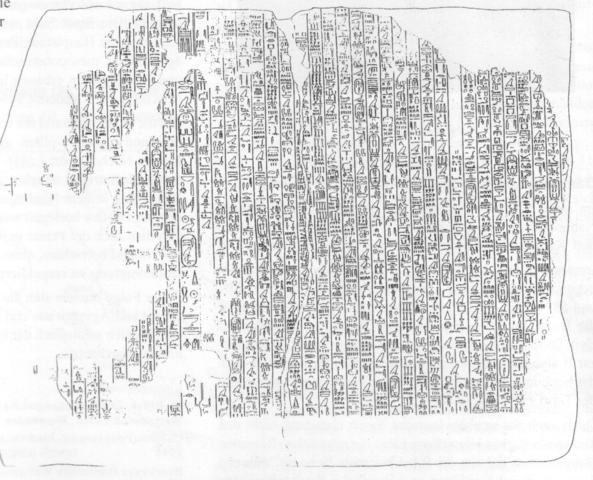

The stelae of Ancient Egypt served many purposes, from funerary, to marking territory, to publishing decrees. Egyptians were well known for their stelae, the earliest of which date back to the mid-to-late third millennium BCE. Images and text were intimately interwoven and inscribed, carved in relief, or painted on the stelae. While most stelae were taller than they were wide, the slab stelae took a horizontal dimension and were used by a small list of ancient Egyptian dignitaries or their wives. The huge number of stelae surviving from ancient Egypt constitute one of the largest and most significant sources of information on those civilizations.

Funerary stelae were generally built in honour of the deceased and decorated with their names and titles. While some funerary stelae were in the form of slab stelae, this funerary stela of a bowman named Semin (c. 2120-2051 BCE) appears to have been a traditional vertical stelae.

Slab stelae, when used for funerary purposes, were commonly commissioned by dignitaries and their wives. They also served as doorway lintels as early as the third millennium BCE, most famously decorating the home of Old Kingdom architect Hemon.

Stelae also were used to publish laws and decrees, to record a ruler’s exploits and honours, mark sacred territories or mortgaged properties, or to commemorate military victories. Much of what we know of the kingdoms and administrations of Egyptian kings are from the public and private stelae that recorded bureaucratic titles and other administrative information. One example of such stelae is the Annals of Amenemhat II, an important historical document for the reign of Amenemhat II (r. 1929–1895 BCE) and also for the history of Ancient Egypt and understanding kingship in general.

Many stelae were used as territorial markers to delineate land ownership. The most famous of these would be used at Amarna during the New Kingdom under Akhenaten. For much of Egyptian history, including the Middle Kingdom, obelisks erected in pairs were used to mark the entrances of temples. The earliest temple obelisk still in its original position is the red granite Obelisk of Senusret I (Twelfth Dynasty) at Al-Matariyyah in modern Heliopolis. The obelisk was the symbol and perceived place of existence of the sun god Ra.