Foundation Myths

The Romans relied on two sets of myths to explain their origins: the first story tells the tale of Romulus and Remus, while the second tells the story of Aeneas and the Trojans, who survived the sack of Troy by the Greeks. Oddly, both stories relate the founding of Rome and the origins of its people to brutal murders.

Romulus killed his twin brother, Remus, in a fit of rage, and Aeneas slaughtered his rival Turnus in combat. Roman historians used these mythical episodes as the reason for Rome’s own bloody history and periods of civil war. While foundation myths are the most common vehicle through which we learn about the origins of Rome and the Roman people, the actual history is often overlooked.

The Historical Record

Archaeological evidence shows that the area that eventually became Rome has been inhabited continuously for the past 14,000 years. The historical record provides evidence of habitation on and fortification of the Palatine Hill during the eighth century BCE, which supports the date of April 21, 753 BCE, as the date that ancient historians applied to the founding of Rome in association with a festival to Pales, the goddess of shepherds. Given the importance of agriculture to pre-Roman tribes, as well as most ancestors of civilization , it is logical that the Romans would link the celebration of their founding as a city to an agrarian goddess.

Romulus, whose name is believed to be the namesake of Rome, is credited for Rome’s founding. He is also credited with establishing the period of monarchical rule. Six kings ruled after him until 509 BCE, when the people rebelled against the last king, Tarquinius Superbus, and established the Republic. Throughout its history, the people—including plebeians , patricians , and senators—were wary of giving one person too much power and feared the tyranny of a king.

Pre-Roman Tribes

The villages that would eventually merge to become Rome were descended from the Italic tribes. The Italic tribes spread throughout the present-day countries of Italy and Sicily. Archaeological evidence and ancient writings provide very little information on how—or whether—pre-Roman tribes across the Italian peninsula interacted.

What is known is that they all belonged to the Indo-European linguistic family, which gave rise to the Romance (Latin-derived) and Germanic languages. What follows is a brief history of two of the eight main tribes that contributed to the founding of Rome: the Latins and the Sabines. Information about a third culture, the Etruscans, is found in Chapter 7.

The Latins

The Latins inhabited the Alban Hills since the second millennium BCE. According to archaeological remains, the Latins were primarily farmers and pastoralists. Approximately at the end of the first millennium BCE, they moved into the valleys and along the Tiber River, which provided better land for agriculture.

Although divided from an early stage into communities that mutated into several independent, and often warring, city-states , the Latins and their neighbors maintained close culturo-religious relations until they were definitively united politically under Rome. These included common festivals and religious sanctuaries.

The Latins appear to have become culturally differentiated from the surrounding Italic tribes from about 1000 BCE onward. From this time, the Latins’ material culture shares more in common with the Iron Age Villanovan culture found in Etruria and the Po valley than with their former Osco-Umbrian neighbors.

The Latins thus shared a similar material culture as the Etruscans. However, archaeologists have discerned among the Latins a variant of Villanovan, dubbed the Latial culture.

The most distinctive feature of Latial culture were cinerary urns in the shape of huts . They represent the typical, single-room abodes of the area’s peasants, which were made from simple, readily available materials: wattle-and-daub walls and straw roofs supported by wooden posts. The huts remained the main form of Latin housing until the mid-seventh century BCE.

The Sabines

The Sabines originally inhabited the Apennines and eventually relocated to Latium before the founding of Rome. The Sabines divided into two populations just after the founding of Rome. The division, however it came about, is not legendary.

The population closer to Rome transplanted itself to the new city and united with the pre-existing citizenry to start a new heritage that descended from the Sabines but was also Latinized. The second population remained a mountain tribal state, finally fighting against Rome for its independence along with all the other Italic tribes. After losing, it became assimilated into the Roman Republic.

There is little record of the Sabine language. However, there are some glosses by ancient commentators, and one or two inscriptions have been tentatively identified as Sabine. There are also personal names in use on Latin inscriptions from the Sabine territories, but these are given in Latin form. The existing scholarship classifies Sabine as a member of the Umbrian group of Italic languages and identifies approximately 100 words that are either likely Sabine or that possess Sabine origin.

Ancient Roman society was based on class-based and political structures, as well as by religious practices.

Social Structure

Life in ancient Rome centered around the capital city with its fora, temples, theaters, baths, gymnasia, brothels, and other forms of culture and entertainment. Private housing ranged from elegant urban palaces and country villas for the social elites to crowded insulae (apartment buildings) for the majority of the population.

The large urban population required an endless supply of food, which was a complex logistical task. Area farms provided produce, while animal-derived products were considered luxuries. The aqueducts brought water to urban centers, and wine and oil were imported from Hispania (Spain and Portugal), Gaul (France and Belgium), and Africa.

Highly efficient technology allowed for frequent commerce among the provinces. While the population within the city of Rome might have exceeded one million, most Romans lived in rural areas, each with an average population of 10,000 inhabitants.

Roman society consisted of patricians, equites (equestrians, or knights), plebeians, and slaves. All categories except slaves enjoyed the status of citizenship.

In the beginning of the Roman republic, plebeians could neither intermarry with patricians or hold elite status, but this changed by the Late Republic, when the plebeian-born Octavian rose to elite status and eventually became the first emperor. Over time, legislation was passed to protect the lives and health of slaves.

Although many prostitutes were slaves, the bill of sale for some slaves stipulated that they could not be used for commercial prostitution. Slaves could become freedmen—and thus citizens—if their owners freed them or if they purchased their freedom by paying their owners. Free-born women were considered citizens, although they could neither vote nor hold political office.

Pater Familias

Within the household, the pater familias was the seat of authority, possessing power over his wife, the other women who bore his sons, his children, his nephews, his slaves, and the freedmen to whom he granted freedom. His power extended to the point of disposing of his dependents and their good, as well as having them put to death if he chose.

In private and public life, Romans were guided by the mos maiorum, an unwritten code from which the ancient Romans derived their social norms that affected all aspects of life in ancient Rome.

Government

Over the course of its history, Rome existed as a kingdom (hereditary monarchy), a republic (in which leaders were elected), and an empire (a kingdom encompassing a wider swath of territory). From the establishment of the city in 753 BCE to the fall of the empire in 476 CE, the Senate was a fixture in the political culture of Rome, although the power it exerted did not remain constant.

During the days of the kingdom, it was little more than an advisory council to the king. Over the course of the Republic, the Senate reached the height of its power, with old-age becoming a symbol of prestige, as only elders could serve as senators. However the late Republic witnessed the beginning of its decline. After Augustus ended the Republic to form the Empire, the Senate lost much of its power, and with the reforms of Diocletian in the third century CE, it became irrelevant.

As Rome grew as a global power, its government was subdivided into colonial and municipal levels. Colonies were modeled closely on the Roman constitution, with roles being defined for magistrates, council, and assemblies. Colonists enjoyed full Roman citizenship and were thus extensions of Rome itself.

The second most prestigious class of cities was the municipium (a town or city). Municipia were originally communities of non-citizens among Rome’s Italic allies. Later, Roman citizenship was awarded to all Italy, with the result that a municipium was effectively now a community of citizens. The category was also used in the provinces to describe cities that used Roman law but were not colonies.

Religion

The Roman people considered themselves to be very religious. Religious beliefs and practices helped establish stability and social order among the Romans during the reign of Romulus and the period of the legendary kings. Some of the highest religious offices, such as the Pontifex Maximus, the head of the state’s religion—which eventually became one of the titles of the emperor—were sought-after political positions.

Women who became Vestal Virgins served the goddess of the hearth, Vesta, and received a high degree of autonomy within the state, including rights that other women would never receive.

The Roman pantheon corresponded to the Etruscan and Greek deities. Jupiter was considered the most powerful and important of all the Gods.

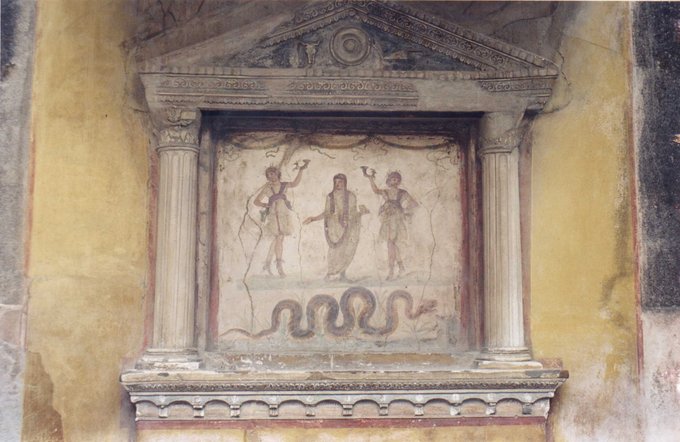

In nearly every Roman city, a central temple known as the Capitolia that was dedicated to the supreme triad of deities: Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva (Zeus, Hera, and Athena). Small household gods, known as Lares, were also popular.

Each family claimed its own set of personal gods and laraium, or shines to the Lares, are found not only in houses but also at street corners, on roads, or for a city neighborhood.

Roman religious practice often centered around prayers, vows, oaths, and sacrifice. Many Romans looked to the gods for protection and would complete a promise sacrifice or offering as thanks when their wishes were fulfilled. The Romans were not exclusive in their religious practices and easily participated in numerous rituals for different gods. Furthermore, the Romans readily absorbed foreign gods and cults into their pantheon.

With the rise of imperial rule, the emperors were considered gods, and temples were built to many emperors upon their death. Their family members could also be deified, and the household gods of the emperor’s family were also incorporated into Roman worship.